Teaching Black History Through Play: Beyond February

Black history isn't a single month—it's an integral thread woven throughout American history, science, literature, and culture. Yet many classrooms still confine Black history education to February, treating it as supplemental rather than essential. Young children deserve to see Black excellence, innovation, and resilience reflected in their everyday learning materials, not relegated to a special unit. When we integrate Black history into play-based learning throughout the year, we normalize diversity, build cultural competence, and ensure all children see themselves and others represented in their education.

Why Play-Based Learning Matters for History Education

Young children aren't developmentally ready for abstract historical concepts or complex timelines. They learn best through concrete, hands-on experiences that connect to their immediate world. Play provides the perfect vehicle for introducing historical figures and concepts in age-appropriate ways.

When a four-year-old completes a puzzle featuring African American inventors, they're not memorizing dates or analyzing historical significance. They're building spatial reasoning skills while becoming familiar with faces and names. They're learning that Black people invented things they use every day. That foundational exposure creates schema—mental frameworks—that later, more complex learning can build upon.

Research in early childhood education consistently shows that children develop attitudes about race and difference by age three. By kindergarten, they've absorbed societal messages about who matters, who's important, and who's represented. Intentionally including Black history in everyday play materials counteracts the implicit bias that comes from representation gaps.

Starting with Inventors and Innovators

African American inventors have created countless items that children encounter daily, yet most children never learn who invented the things they use. This creates a powerful entry point for age-appropriate Black history education.

Garrett Morgan invented the traffic light. Every time children see a stoplight, they can remember Morgan's contribution to safety. His story connects to their everyday experiences while teaching that Black inventors solved real-world problems.

George Washington Carver revolutionized agriculture and created hundreds of products from peanuts. His story connects to science, nutrition, and environmental stewardship—themes already present in early childhood classrooms.

Lonnie Johnson invented the Super Soaker water gun. This fact delights children and demonstrates that Black inventors create fun, playful things, not just serious inventions.

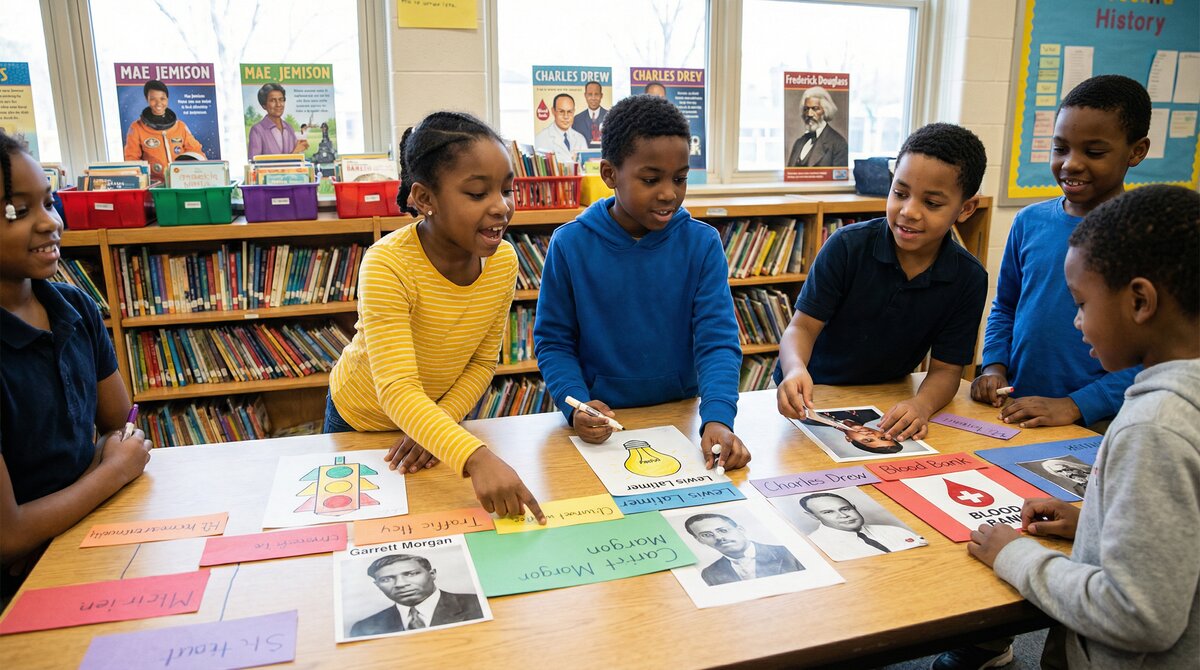

When children play with puzzles, games, or learning materials featuring these inventors, they absorb the message that Black people are innovators, problem-solvers, and creators. This representation matters for all children—Black children see themselves reflected as capable and brilliant, while children of other races learn to associate Black people with intelligence and achievement.

Integrating Black History into Literacy Learning

Literacy instruction provides natural opportunities to integrate Black history throughout the year. The books you choose, the names you use in examples, and the images in learning materials all send messages about whose stories matter.

Diverse book selection: Build a classroom library that includes Black authors and characters as a matter of course, not just during February. Books by Jacqueline Woodson, Kadir Nelson, Andrea Davis Pinkney, and Vashti Harrison should sit alongside other favorites. Children should encounter Black characters in everyday stories about friendship, family, and growing up—not only in stories about slavery or civil rights.

Inclusive learning materials: When selecting phonics cards, sight word games, or alphabet posters, choose materials that feature diverse representation. If the picture for "D" shows a dark-skinned child playing drums, and "T" shows a Black teacher, children absorb the message that Black people belong in all roles and contexts.

Author studies: When you do author studies, include Black authors. Young children can learn about Ezra Jack Keats, who wrote "The Snowy Day," or Leo and Diane Dillon, who illustrated countless beloved children's books. Discussing authors helps children understand that real people create the books they love.

Age-Appropriate Approaches by Developmental Stage

Ages 3-4 (Preschool): Focus on representation and exposure. Use puzzles, games, and books that feature Black children and families in everyday situations. Introduce one or two inventors through simple stories: "This is Garrett Morgan. He invented the traffic light that helps keep us safe." Keep it concrete and connected to their world.

Ages 5-6 (Kindergarten): Build on exposure with simple cause-and-effect stories. "George Washington Carver was a scientist who studied plants. He discovered that peanuts could be made into many different things. Now we have peanut butter!" Connect inventors to children's interests—if they love building, talk about Lewis Latimer's work on light bulbs and electrical systems.

Ages 7-8 (Early Elementary): Introduce problem-solving narratives. "Marie Van Brittan Brown noticed that police took a long time to respond to emergencies in her neighborhood. She invented the home security system so people could see who was at their door and call for help faster." This age can understand that inventors identified problems and created solutions, building critical thinking alongside historical knowledge.

Beyond Inventors: Expanding the Narrative

While inventors provide an accessible entry point, Black history encompasses far more than innovation and invention. As children grow, gradually expand the narratives they encounter.

Artists and musicians: Introduce children to Jacob Lawrence's vibrant paintings, Romare Bearden's collages, or Faith Ringgold's story quilts. Play music by Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong, or contemporary artists during center time. Art and music provide joyful, accessible entry points to Black cultural contributions.

Athletes and explorers: Stories of Jackie Robinson, Wilma Rudolph, or Mae Jemison (the first Black woman in space) inspire children while teaching perseverance and courage. These narratives show Black excellence across domains while introducing age-appropriate discussions of overcoming obstacles.

Everyday heroes: Not all historical figures need to be famous. Share stories of Black teachers, doctors, community leaders, and families who contributed to their communities. This helps children understand that history is made by ordinary people doing extraordinary things.

Creating an Inclusive Classroom Environment

Integrating Black history isn't just about what you teach—it's about the environment you create. The images on your walls, the materials in your centers, and the examples you use all contribute to whether children feel seen, valued, and represented.

Visual representation: Ensure your classroom displays include Black children, families, and historical figures year-round. Alphabet posters, number charts, and classroom job labels should all reflect diversity. When children see Black people in positions of authority and achievement throughout their learning space, it normalizes excellence.

Dramatic play materials: Stock your dramatic play area with dolls, action figures, and dress-up clothes that represent diverse skin tones and hair textures. Include books about Black families in the home living center. These materials allow children to practice empathy and perspective-taking through play.

Inclusive language: Use examples that include Black children naturally. "If Jamal has three apples and Keisha gives him two more..." This small choice signals that Black children belong in all contexts, not just stories specifically about race.

Addressing Common Concerns

"Aren't children too young to learn about racism?"

Children aren't too young to learn about Black excellence, innovation, and achievement. You don't need to discuss slavery or racism to teach about Black inventors and artists. Start with positive representation. As children mature, you can gradually introduce age-appropriate discussions of challenges these figures overcame.

"I don't want to make mistakes or say the wrong thing."

Imperfect action beats perfect inaction. Start small—choose one diverse book per week, add one puzzle featuring Black inventors, or learn about one Black artist to share with your class. Growth comes from trying, reflecting, and improving, not from waiting until you feel completely prepared.

"What if parents object?"

Frame Black history education as part of comprehensive, accurate history instruction. You're not teaching a political agenda—you're ensuring children learn complete, truthful history. Most resistance comes from misunderstanding. Share your approach proactively, explaining that you're teaching about inventors, artists, and historical figures who happen to be Black, integrated naturally throughout the curriculum.

Practical Implementation: A Year-Round Approach

September: As you set up your classroom, ensure diverse representation in all materials. Introduce yourself and your teaching philosophy, including your commitment to inclusive education.

October-November: During units on community helpers, include Black doctors, teachers, firefighters, and police officers. When studying fall harvests, discuss George Washington Carver's agricultural innovations.

December-January: During winter science units, discuss Lewis Latimer's work on light bulbs and electrical systems. Read books by Black authors during your winter reading units.

February: While you can certainly do deeper dives during Black History Month, it shouldn't be the only time children encounter Black history. Use February to explore themes more deeply, not to introduce them for the first time.

March-June: Continue integrating Black artists during art units, Black athletes during physical education, and Black authors during literacy instruction. Make representation a consistent thread, not a special event.

The Impact of Representation

When Black children see themselves reflected in learning materials, it sends a powerful message: you belong here, your history matters, people who look like you have always been brilliant and capable. This representation builds identity, confidence, and academic engagement.

For children of other races, consistent exposure to Black excellence builds respect, empathy, and accurate understanding. It counteracts the single-story narrative that reduces Black history to slavery and struggle. Children learn that Black people are inventors, artists, scientists, and leaders—not just historical victims but active shapers of the world they live in.

This isn't about political correctness or checking diversity boxes. It's about accuracy. Black history is American history. Black inventors shaped modern life. Black artists enriched American culture. Black scientists advanced human knowledge. Teaching complete, honest history that includes these contributions isn't special—it's simply correct. And when we integrate this complete history into play-based learning from the earliest ages, we raise a generation that sees diversity not as something to celebrate once a year, but as the ordinary, unremarkable fabric of American life.